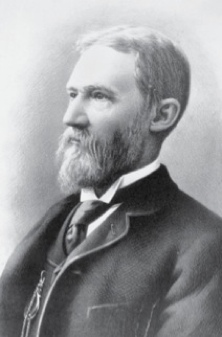

Samuel Griffith was eight when he migrated with his family from Wales to Queensland in 1853. After an education at several different schools in Queensland, Samuel went to the University of Sydney. He was an outstanding student, and later studied law in Brisbane, becoming a lawyer in 1867. He married Julia Thomson in 1870, and two years later entered politics when he was elected to the Queensland Legislative Assembly.

Samuel Griffith was twice Premier of Queensland and had two knighthoods bestowed on him, which entitled him to be called Sir Samuel Griffith. As a politician, he introduced laws to prevent more South Pacific Islander labour being imported to Queensland, and passed a bill to legalise trade unions. He represented Queensland at the Colonial Conference in London in 1887 and impressed delegates with his ideas about trade. In 1891, he authorised the use of the military to break the Shearers’ Strike that had put Queensland in turmoil.

In the same year, at the Sydney Constitutional Convention, he used his fine legal mind to draft Australia’s first Constitution. His main ideas are still in Australia’s Constitution today. As Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Queensland, Samuel Griffith drafted Queensland’s Criminal Code.

Samuel Griffith was a great supporter of Federation and campaigned for it boldly. After Federation, he became the first Chief Justice of the High Court, the highest legal position in Australia. Samuel Griffith retired from the High Court in 1919. He died the following year, aged 75.